A successful career in the music industry is a feat that often takes years or even decades to achieve. Today’s guest, however, started working professionally as soon as he stepped out of high school. Joining Rich Redmond today is legendary Nashville drummer Chad Cromwell. He has worked with some of the biggest names in the industry, Paul McCartney, Neil Young, and Joan Baez, just to name a few. He started playing drums by the age of eight, then worked with local garage bands at the age of 12, and was working professionally in London after graduating. With a life-long career in the music scene, Chad has more than one lesson to share and plenty more fun anecdotes to tell, from failed opportunities to big breaks. He also talks a bit about his recent Rolling Stone interview with Andy Greene and being recognized as an Unknown Legend in the industry. Don’t miss a beat and get to know more about Chad by tuning in on this episode!

Listen to the podcast here:

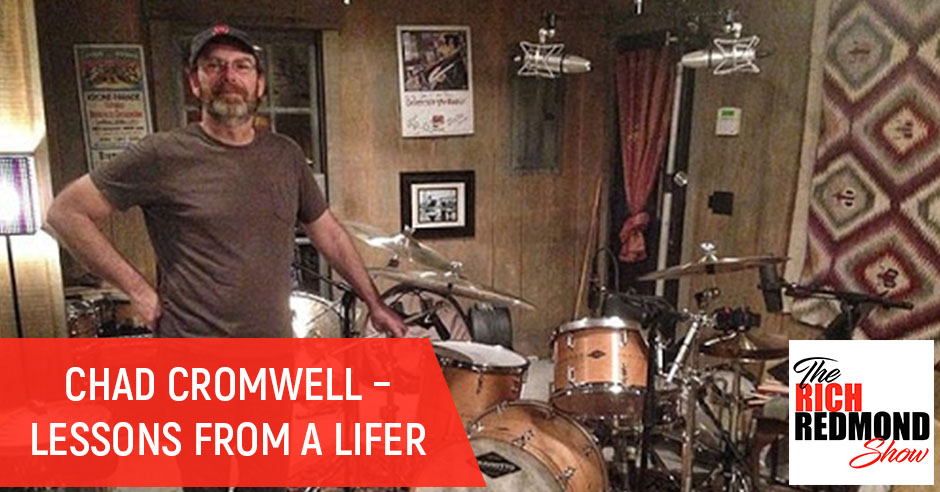

Chad Cromwell – Lessons From A Lifer

In this episode, legacy drumming with Neil Young, Joe Walsh, Bobby Ray and more of Chad Cromwell.

—

What’s up, rock and rollers. It’s that time. It’s another exciting episode of the Rich Redmond Show coming to you from two cities. My guest is Music City USA, my sidekick cohort, news, co-producer Jim McCarthy from JimMcCarthyVoiceovers.com who’s also from Music City. I’m in sunny Los Angeles. Jim, how have you been?

Doing well. You’ve got the sound effects at the ready.

Whatever settings you did on your box to get those sound effects to work are great.

I’m playing with the settings on my box.

I knew you would go there. Do you see why I keep him around? Jim, let’s get right into this. This guy needs no introduction but for the folks in the audience that might not be drummers, drummers know who this guy is. This is heavy. This is velvet rope crap. He’s toured and recorded with longtime drummers. Folks like Neil Young, Mark Knopfler, Joe Walsh, Crosby, Stills & Nash. You can hear him with all the usual crew of characters like the Chesneys, the Mirandas, the Blakes and the Traces. Hailing originally from Paducah, Kentucky, our friend Chad Cromwell. How are you?

I’m well. Thanks for having me on board.

It’s funny. Remind me when you moved to Nashville. It was several times that you’ve lived in Nashville over the years. I moved to Nashville in 1997 and our drums are parked over at the same place, Drum Paradise. Everyone hears about this urban legend of this guy, Chad Cromwell. One of the most working drummers in Nashville but I never get the run into you. We’re always sitting behind a set of drums so it’s long overdue. There was one year that I did this two-part spread for Rhythm Magazine on the drummers of Nashville. You’re so busy that you couldn’t even make this session.

I got lucky. I had a lucky week that week. I don’t know.

You’ve been at this for so long. We go way back. You were born in Paducah but then you consider yourself a Memphian.

By way of Clarksdale, Mississippi.

You’ve lived in London, Los Angeles and Nashville. You’ve lived on airplanes and tour buses.

I still do.

I don’t know if you thought about it as a business model. It was certainly for me. It was like, “In Nashville, you can very much well be segregated. I’m a songwriter. I’m a producer. I’m a touring musician. I’m a studio musician.” You have always played on people’s records. You have always been willing to jump on the bus to take the music to the people, which I may have stolen from you. Kenny Aronoff had that same business model. I love it. I feel like each of those things feeds one another. Am I right in saying that?

By my way of thinking, you’re spot on. It sounds like what you feel. There are lots of guys. To me, the way that I approach music and the way about music, one feeds the other and there’s no particular order of priority. It’s just that one feeds the other. There’s physical energy that playing live has that you cannot reproduce in a studio. It’s not possible.

You can access the spirit of that but the thing of being in front of whether it’s 50 people in Douglas Corner or 500,000 people at the Detroit Grand Prix or whatever it is, something happens when you’re in front of an audience that elevates your whole psyche. All your synopses are banging because you’re influenced by eyesight, the way people are physically reacting to what you’re doing up there with your mate, the space that you’re in and all of it. It influences and informs the way you play.

In the studio, we have a whole different set of construction rules. We know that we’re in a singular position to go into like, “Here’s the song. Here’s the demo of the song.” If it’s a demo session, “Here’s the acoustic vocal version of the song and this is what we want to go for.” Our job is to execute that for someone. We’re inside of a box that’s inside of a box that has a recording, a Pro Tools rig set up in it and our gig is to make sure that song gets documented.

Playing live helps me to bring some energy to a recording session where I’ll hopefully try to access that place where I know you understand, which is access to a place where we’re no longer thinking. Access the place where it’s a spiritual expression. It’s in the moment and influenced by a musical conversation that’s happening among the other folks in the room with us greater than the sum of our parts. It’s that thing, whatever you call that. Without the live piece, the touring, getting on the airplanes, tour buses, missing home and loved ones and all of that, to me, recording is like any job. It’s like a journeyman craft that we go and we do on a daily basis and we do the best job we can with that.

The way that I approach music and the way I think about music is one feed the other. There’s no particular order of priority. Share on X

If all I see is a pair of headphones, a recording studio and nothing else, I can assure you that a guy like me is going to get bored. If I’m bored, I’m not giving the client, the artist or the producer what they need and expect from me. The gig is worth the risk of leaving that security place of, “I’m a recording musician. It’s 9:00 to 5:00 but in our case, it’s a 10:00 AM to 9:00 PM thing on a busy day. This is what I do. I do nothing more Monday through Friday and weekends off.” This is sounding like an insurance salesman’s game, a good one but it’s still one-dimensional.

The live thing pulls me completely away from all of that and it gets me into the unknown space of working for guys like Neil where I have no idea how to measure what’s getting ready to happen. There’s a level of consciousness that is absolutely impossible to duplicate with a video. It’s not possible. I’ve done it with Neil, it’s not the same thing but I rely on it. It’s life blood to me but so is the studio. It’s a duality. I’ve got to have both.

To me, they’re completely different and completely the same. I know a lot of people overthink it. I’m like, “We’re in service of the music. We’re making the producer, the artist, the songwriter and the label. We’re working for them.” It’s, “Yes, sir.” “Yes, ma’am.” When you get on the road, it’s the same thing, getting into the mindset. I’ve been working with the same guy for over 21 years, which is rarefied air as you know. The music business is the Wild Wild West. There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t appreciate that. Whether it’s in the studio or on the road, I know what that expectation is from that entire camp. Know the song, show up, bring the energy, smile, heads up, lay down, stay out of the way. We know what to do and it’s a matter of getting up there every day and executing with a smile on our faces.

You’re one of the best at that. I’ve seen you play and you’ve got a thing about you that is exciting to watch and it’s cool. What you’ve done with Jason is a remarkable thing. In our country world, you guys have taken what I consider to be the concept of what a rock and roll band is all about, which is you’re a band. Michael has done such a great thing by keeping you guys together as a unit and it sounds like it. You should be proud of that.

Thank you so much.

You can even hear the trademarks on other artist’s records that they play on.

I do appreciate it. There’s so much in this industry that comes down to gratitude and humility. I’m trying not to let moss grow on the log, trying to stay relevant, picking those ripe grapes and turning them into fine wine. You’re no stranger to this. You are a band guy. You know how to operate in a band and read the room. You’re the conductor, you’re a psychologist, you’re giving direction and you’re taking direction. It starts for you in Memphis. You’re listening to guys like Al Jackson, Ringo, Buddy Rich. Are you self-taught? Did you take lessons?

Self-taught. I started playing drums when I was eight but I did it purely because the kid down the street got Christmas presents for him and his brother from Sears. One of them got the little Silvertone Guitar with the amp built into the case and the other guy got a Red Sparkles set of Sears Drums. I’m not sure who made them but I went down there to see what Santa Claus brought when I was eight. I thought Santa brought it to them.

Did you instinctively know what to do when you got on the kit?

That’s the weird thing. When I got there, I went straight to the drum set, sat down behind the drum set and I started playing a beat. It felt completely comfortable. It didn’t feel foreign to me at all. My mom was a classical pianist, a teacher for many years and an organist. She was also great with the pipe organ so she played in churches. I grew up underneath a baby grand piano from the time I was a baby.

The piano made no sense to me ever. I didn’t want to go there. I found these drums awesome. I never viewed drums as anything other than something fun to do. I wanted to be a baseball player. That’s all. I was never aspirational about the drums until I was about 14 or 15, somewhere right around there, I got turned on to it. I was like, “This is more than something to pass the time until the next baseball game.”

The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964, was that a game-changer for you? You were only 7 or 8 years old.

In front of the TV screen. Seeing those Black Oyster Ludwig sitting up there, it bit you. The way that Ringo layed into that kit was Ringo. I could see that little bandstand move in and I could see him putting every ounce of his energy into that kit. It was a game-changer without question.

He presented at the Grammys 2021 and even my girlfriend was making noise. I said, “That dude is 80 years old.” She goes, “He looks like he’s 55 years old.” You’ve worked with McCartney. I’ve seen a video when you jumped on stage. Have you ever worked with Ringo yet?

I’ve never worked with him. My wife does though. She sings on all of this stuff.

Your wife’s a session singer?

She’s a badass session singer. Her name is Windy Wagner. Look her up.

How did you kids meet?

Lessons From A Lifer: I’m a real believer in finding destiny, and sometimes getting to that can kick your ass a million different ways before you realize that the journey you’re on is exactly the one you’re supposed to be on.

With Joe Walsh.

Was she one of the chick singers on the stage?

Yeah. It changed my life.

Were you married before? Is this number two?

I was married before. I was married for 25 years. I was in a 31-year relationship.

I usually will get into that a little bit on the show, tipping our hat to the idea of the creative arts, the travel and the lack of normal schedules are not for the faint of heart.

What we did is particularly taxing for traditional family life. It’s a hard thing to do. Sadly, my kids had to go through some tough years because of all of the stresses that a career can place on family life. Also, the way that we as humans evolve, sometimes we evolve in a different direction and that’s what happens. It was what it was and it came to an end. As things do, I’m a real believer in finding destiny. Sometimes getting to that can kick your ass a million different ways before you realize that the journey that you’re on is exactly the one you’re supposed to be on. Through the refinement phase of that, it’s uncomfortable. I feel a lot of gratitude to find myself where I am at this stage of my life creatively, musically, romantically and as a father in all ways. I’m a better dad now than I’ve ever been. My kids are grown.

What did they get into? Have you got any musicians?

I got two natural-born musicians that watch their dad want no part of being in the music business. It’s too hard. They don’t want to do it.

That’s good because nothing else is going to be an option. You’ve got to have that.

Do you know who Eddie Izzard is? Death or cake. Have you ever seen his stand-up routine?

Yeah, British comedian.

He’s in a horribly bad drag outfit standing on stage doing stand-up comedy and he does this whole history of the world stand-up bit that’s one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen in my life. There’s this whole English thing. It’s like, “What are my options here? Death or cake? Which do you prefer? There’s only one choice here.” That’s what we do as drummers in this business. You have to be a little crazy, a little bit overly determined and self-confident to do this because there’s no, “I’ll do this job over here and I’m going to be a session guy,” or, “I’m going to be a touring guy but I’m not going to do the grunt stuff where there’s no money in it. I’m only going to do the big tours. I only want that.” Guess how you get there. You climb into the back of the van with the rest of us.

You did that. You first got on my radar. This may bring back some memories for you but there was a Radney Foster record called See What You Want to See, 1998. Around the same time in 1999, I got the touring job with Pam Tillis and this was the first time I had someone twisting off my water bottle and setting up my drums. Fans on one. Fans on three. It was amazing. I was like, “This is awesome.” You played on the record Thunder & Roses so you were on my radar. You’re playing on this Radney Foster record.

It was eye-opening because it was a masterclass in how you play for a singer-songwriter. The drum tones were so open. I don’t think there was moongel in sight. It was gorgeous. I was like, “Check out this drummer. He doesn’t play a crash cymbal where you want to hear one and he plays a crash cymbal where you would never expect one.” Maybe out of the blue, there’s some floor tom hit. All incredibly musical stuff but different from what I was hearing with Eddie, Lonnie and with the folks I was hearing on Music Row. That’s where you first got on my radar.

Nashville is divided into two seasons for me before I was living here. I was coming up here in the early ‘80s doing contemporary Christian projects. I got to know guys like Jerry McPherson and Mike Brignardello. The list goes on in all these great players in that genre. I never could quite get my head around, “I don’t want to go to Nashville to play on contemporary Christian records. I don’t think so.” Mike Brignardello gets up here. He has his apartment, called the phone, plugged in. That’s how far back this goes.

That’s the answering machine.

He starts coaching me a little bit gradually, year by year on, “Here’s how you do this. If you want to get up here and get into the country scene, here’s how you do this.” Mike started transitioning out of the contemporary Christian world into the country thing so I followed him. Michael Rhodes was the last straw. Michael and I played well together. During a session in Memphis, he said “You’ve got to do this.”

There’s physical energy that playing live has that you cannot reproduce in a studio. Share on X

“It’s three hours down the road. Pack your stuff.”

“Let’s go. What are you waiting for?” Fast forward, what I consider to be, “I live in Nashville. I am going to do this session thing. I’m committed to this,” was a Joan Baez record that Wally Wilson and Kenny Greenberg produced. I went to the session and Kenny hired me. From what he told me anyway, he said, “I like the way you play the eighth note on Rockin’ in the Free World so I want you to play on this record.” When he tells me that it’s a Joan Baez record, I’m thinking, “You like the way my eight-note sounds on Rockin’ in the Free World so you want me to play on a Joan Baez record?” It was funny to me and I thought, “I’ll do it. Thank you.” Treasure Island Studio is where we did it. The bass player that was hired for the gig was Willie Weeks. I walk in the door and he’s like, “I’m Willie.” I was going, “My god.” It was exciting.

When you think about it, we were talking about a British comedian but you lived in London. You were in high school and graduated. As soon as you graduate, you get a gig with a signed act. You’re living in London and for a while you were going back and forth between Nashville and Los Angeles. You were going where the opportunities are. Ever since you were a senior in high school, you haven’t missed a meal. You’ve been playing the drums professionally.

I haven’t stopped. One way or another, I’ve managed to keep my feet moving forward. The London thing was a trip because it was two weeks after I graduated from high school. I got this gig, largely because the two other principals in the band were originally from Memphis living in London. One was Robert Johnson who was the guitar player in John Entwistle’s side band called The Ox. David Cochran, the bass player, was playing for an artist called Chris Spedding, a hot rod guitar guy over there. Roy Harper came after that.

These guys were well established over there as Southern boys from the US. In the ‘70s, that had a little bit of juice on it to be from Memphis. I got this gig. I jammed with David when he had come home to visit his family on a holiday break and the next thing I know, it’s like, “Come on. Let’s go. Can you move to London?” I went, “Yeah.” I get over there and we go straight into a studio called Mayfair and we make an album in three days. It’s power-punk trio stuff and it was fun. Elton John’s startup label called Rocket Records was going to sign us. The first two signings of that label were us, Grace Jones and the disco gal.

I went in a space of six months or whatever it was living in London. We’re living in this beautiful brownstone. I’m about to become a rock star and I’m pretty sure there are some big checks coming. We’re going to go on tour with Elton John. I can’t believe it. We were taken out to the Marshall Guitar factory in Bletchley. The guitar player and bass player ordered tons of gear which in the mid-‘70s was desirable stuff to have and it all fell apart. It’s like the business in the stories. It was ridiculous but it was a great. It started me on my path. London’s always on to me.

It makes me think when I’m doing a deep dive for our guests and getting a feel of the whole story. It seems like it came down to you. You have this incredible ability. You have this it-factor playing the drums. People are attracted to your talent and also probably your personality, you’re hanging and all that stuff that people like to talk about but it seems one relationship after another. You’re working with Joe Walsh when you were 30 years old. How did that happen?

That was in ‘86 that I met and started working with Joe. I was still living in Memphis at the time, I got to Nashville in ’90. I was officially in Nashville in ‘99. In ‘86, I met Joe in Memphis and we met at a studio that I worked at fairly frequently. One thing led to the next. A few late-night hangs are unlike what you would expect with Keith Richards. It’s fun and scary all the time. The next thing I know, he calls me and he goes, “Do you want to come to a gig?” I went, “Yeah. What’s going on?”

He goes, “The first thing I need you to do, I need you to come to Dallas. Me and Rick, the bass player, are doing this guest DJ thing in Austin for a week. Why don’t you come down here for the week and when we’re not working on the radio station, doing the show, we’ll get together and we’ll rehearse every day. We’ll work to stuff up.” This is going to be awesome. I fly down and I’m in the hotel with them.

The first day goes by I get a call, “We can’t get together today. Some things have come up. We’ll catch up tomorrow. We’ll make up for lost time tomorrow.” The next day comes. I hung out with them a bit. After the first day later that night, the next day comes more excuses about why we can’t get together and rehearse. I was like, “Where’s Joe?” They’re like, “I don’t know where Joe is but he’s rehearsing.”

Day after day. The pressure is rising with me every day because I’ve got a week to prepare for my first gig with Joe. Long story short, I never did get to rehearse with Joe. All I got to do with Joe was partying with him late at night. We had to get on a plane and fly to Los Angeles early in the morning. We flew to LA, got off the plane, got in a limousine and drove to Irvine to a KLOS annual celebration that’s hosted by Gino Mitchellini who was a big rock and roll DJ for KLOS for years and years. He was a good buddy for quite a few years. This is horrible. This is the worst thing.

My first sure enough big gig is going to burn up in flames. He never got a fair shot at it. We got to the gig. By the time I was due to go on stage, I’m crapping my pants. It’s like, “I can’t believe this is happening.” I finally let go of it and I went, “There’s nothing I can do now. I’m going to go for it. I’ve heard the songs through the years. I know the beginnings and endings. Here we go.” We went and we had an absolute ball. We played as a trio, which is my favorite way to play with Joe. Except for when I met my wife.

How does Joe Vitale fit into all this?

We had some doozies but we had fun and it was total rock and roll. That was the beginning of what is now over a 30-year relationship with Joe. Where Joe Bob fits into this, we all lovingly call Joe Bob is at that time working a lot with CSNY. He was doing other projects and Joe was in some fairly controversial years of his hiatus from the Eagles. They were tough times for Joe. Everyone in his periphery said it was tough. Joe was off doing his thing with CSNY and they were not working together for a minute which is how I got in there.

We eventually got together. I can’t remember exactly when. It was right around ‘89 or ‘90 somewhere around there when we got together in the studio. We went into the studio with Joe. Bill Simcik comes back into the picture to produce it. Joe Bob comes into the picture to play keyboards and some drums on the record. We ended up in Chattanooga on Lookout Mountain. There was a studio up there and we made the Ordinary Average Guy record up there. That’s how I got to know Joe Bob. Subsequent to that and supporting that record. We went on a double bill tour with the Doobie Brothers. Two bands, two drummers in each band and it was a circus. We had a blast. We had a lot of fun together. We got to know those guys well. Those were good times.

Where in good proximity to Rock City were you?

Do you know Chattanooga well?

When you mentioned Lookout Mountain, we’ve been there several times camping. It’s a hard-to-miss mountain. It’s ginormous.

Lessons From A Lifer: As drummers in this business, you have to be a little crazy and a little bit overly determined and self-confident to do this.

If you look at Mountain or whatever that area is called, there’s a village up there and there’s a grocery store and a couple of little sewing shops. It’s a super quiet bedroom community up there. Some folks live up there. That’s where the studio was.

Was it on the Georgia side or Tennessee side?

Tennessee.

Jim, I remember you told me the story of when you were moving to Nashville from Vegas because you were doing radio in Vegas. You were trying to pop your cherry a little bit on listening to modern country music. What were the first acts that you were listening to? Because you might have been listening to Chad years ago.

I’ll tell you exactly how it happened. Courtney and I took our last trip together as a childless couple. We went to Tampa, Florida and the notion of us moving to Nashville the seeds have been planted because we wanted to get out of Vegas. We got to Tampa and started listening to a local country station there. Whatever was on the top 40 playlists on the country power rotation of the time was what we heard. Dierks Bentley, Jason Aldean was brand new. We heard Montgomery Gentry and all those guys. It was a good time to get into it because songs resonated with us.

To me, it’s Southern rock country. All the bands and artists you mentioned were, interestingly, band-oriented sounding records.

It was rock but not.

To hear got a lot of leaving left to do with the four and the floor beat.

Once a drummer.

This was like playing Rush songs for crying out loud.

That was Steve Brewster on that track. When you think about Steve, you think about contemporary Christian music. He was starting to venture into those worlds. When you start looking at this list, Jim, check this out Dave Stewart, Vince Gill, Amy Grant, Lady A, Diana Krall, Willie Nelson, Jackson Browne, Boz Scaggs, Wynonna, Trisha Yearwood, Miranda Lambert, Bonnie Raitt. These are the who’s who of the music business. I tell students, “You’re going to run into celebrities. You’re probably going to end up working for celebrities. Remember this, they put on their jeans one leg at a time. They poop and they pay taxes. They’re normal people.”

Here’s the one thing though. Typically, around here they will treat you the same way. It’s like, “We’re people.” You will every now and then get the one that’s got the chip on their shoulder.

They’re not usually at the top of their game. They’re usually somewhere in the middle. Am I right? Maybe, in my experience.

Generally speaking, you’re right. I’m hesitating whether or not to tell the story or not. It was country music at all. Here’s how I’ll do it. Amnesty International, 1990, Santiago, Chile. I was there for Jackson Browne who was appearing as one of the acts in the Amnesty International concert. It was a big deal. The host of the whole thing was staying along with Peter Gabriel and Ruben Blades. It was those three hosts of the event.

There’s this breezeway, this old soccer stadium where the concert was held and in the breezeway was this long row of what became a series of dressing rooms, maybe 10 or 15 dressing rooms because there were acts after acts going on stage and this went on for two days. We’re in our little dressing room and we’re waiting to go on. In this breezeway, there are all these people coming and going like the crew guys, press people, bands coming and going. It was a crowded breezeway. It was a long hallway.

All of a sudden, this commotion from way down there starts happening. I was like, “What’s going on?” It’s almost like the parting of the seas is happening but it was happening so far away that we couldn’t tell what it was or what was going on. The parting of the seas continues and gets closer and closer. When he gets about 25 or 30 feet away, we figure out what’s going on. It’s Sting and he’s surrounded by probably ten bruisers with guns and a platoon of security. He walked in with his head down. There was no communication with anybody. He blows through the crowd. He won’t speak to anybody. This is one of the hosts. He blows through. We found out a little bit later that he doesn’t talk to anybody. He doesn’t want to communicate. We found out a little bit later that he won’t talk to anybody. He doesn’t want to communicate. Whatever. He won’t talk to anybody.

The sea comes back together after he passes, life goes back to normal. A few minutes later, there’s a knocking sound. One of the guys in the band goes to the door, opens the door and there’s Peter Gabriel standing there. He goes, “My name is Peter Gabriel and I’m one of the hosts here. I thought maybe it would be nice if I came by and got to introduce myself to you and see if you guys are comfortable. Is there anything I can do for you?” I’m like, “Are you kidding me? Come on in.”

He comes on in and he could not have been a more lovely host. It’s a total polar opposite way of doing what Jim described. Occasionally you run into these folks. They don’t want to know about you. They’re in their bubble and they’re going to stay in that bubble and nothing’s going to interrupt that. Gabriel comes along, they’ll want to make you a sandwich. That happened to Bob Glaub and I. It was a Stevie Ray Vaughan show at Pine Knob where he died in the helicopter crash.

There’s something that happens when you’re in front of an audience that elevates your whole psyche. Share on X

We had gotten in a day early with Jackson and we didn’t have anything to do. We got invited to come out to Stevie Ray’s show. We came out there and he was pretty newly sober at this time. We came to his show thinking, “I feel a little weird about going into his dressing room. I don’t want to do that.” Bob said, “It’s okay. We know these guys. It’s all good.” I went, “Okay.” We went in there and it was the same thing as Peter. Stevie’s standing there, “Come on in here. How are you doing?” He tried to fix us a sandwich while we were in there and he was about to go on stage.

His mom trained him right. He was being hospitable. Do you guys want cheese or what?

He couldn’t have been a nicer cat. We’re lucky when we get to work with these amazing cats that are also human beings, nice people. Paul McCartney absolutely falls into that category. He couldn’t be a nicer guy. It’s so unnecessary if you’re at a level of success like that, you have nothing to prove. Just be nice. It’s a real welcome thing. I said, “I see way more of that than I see the bad stuff.”

That’s great to hear with the amount of people you’ve worked with. That is awesome. Jim, I’ve got to say, it’s so challenging getting talented people together. It’s like herding cats. Jim’s going to be pulled away. He’s got last-minute coaching. He’s a soccer coach. You’ve got a last-minute game here but so we’re going to stay on. We’re going to talk a little bit but Jim is going to ask you a random question of the day. We can continue talking about drum nerd stuff.

Chad, what still do you wish more people took the time to learn?

Is this a general question of all humanity?

It’s completely random. In general.

Social skills. I would say so. That’s a good one.

Like please and thank you?

Yeah. That’s a start.

There are so many bad drivers everywhere. It’s like, “Can you at least use your turn signal as a courtesy here?”

It plays into what we were talking about social skills.

Common courtesy.

It goes a long way. That’s important in the South. I’m from Connecticut but I’ve noticed that in the South, you’re taught those things at a young age.

I know so many people from other parts of the unknown, out there or wherever. They all say the same thing. How hospitable people are down in this way. It’s general friendliness. It’s a fundamental please and thank you. Be nice to people no matter what or just about no matter what.

That goes far because I say it’s an expectation for you to have this amazing skillset, exceed expectations, be on time and be able to problem-solve with a smile on your face but that thing of, “Can we have a cup of coffee together? Can you take direction without being offended?” All that stuff is so important.

It sure is. It’s super important. I don’t know how to do it any other way than the way I was taught. I try to apply that and sometimes I’m not totally successful but I try anyway.

Jim, great question. I know you got to pop off. Thank you for your time and talent. Everybody, JimMcCarthyVoiceovers.com. We love Jim.

Lessons From A Lifer: We’re lucky when we get to work with these amazing acts that are also human.

Do you want me to leave now?

No. You said that you’ve got to coach a game. You pop off. It’s no big deal. We’re going to keep talking about lugs, diecast hoops and pedal.

Floor times, legs or not? That was the question.

Legs.

It was funny as I was doing some research and I was listening to our buddy Trav from Drum Paradise. I was like, “Nice little drum chat podcast.” It was so cool how he brought up this whole thing about how Nashville is a live rhythm section town and it’s one of the last places on earth where it’s Stax Records or Motown where you got eight guys on the floor counting off the song, look at each other in the whites of each other’s eyes.

Whereas, in Los Angeles outside of TV and film has become such a heavy pop and hip-hop culture of the MPC and using in-the-box instruments that it’s rare to have a rhythm section on the floor. You brought up the idea where you have this new goal and direction for what Los Angeles has to offer. What is this next season of your life? What are you working on?

There are a couple of several things but largely what I’ve gotten into is film and television composition. I have a partner in Los Angeles called Amotz Plessner. He’s a first-generation Israeli and super talented composer. He’s done a lot of stuff through the years. His work has been in a lot of films. Not the least of which would be Avatar. He wasn’t the music director of that film but he made contributions to it and there are pieces of his work that are in it. He’s done all kinds of stuff like big ad campaign stuff. He was with Calvin Klein for years and I did a lot of that. He’s a neighbor that lives around the corner. We met at a party at our next-door neighbor’s place and we started talking.

It was like, “Someday, it would be nice to maybe do some music together.” How many times have we said that to new acquaintances and it never happens? In our case, it did. It was in the form of my wife and I was asked by Amotz to do a series of 90-second pieces of music for the Japanese television market. They were all original compositions and with no particular direction other than think about that, think about Japanese television, the culture and write toward that so we did. That’s how it started.

One thing led to another. Amotz and I got together and decided to write organically with absolutely no agenda attached to it other than we wanted to produce the music organically, stay off the laptop as much as possible and samples and all that. Let’s make the sounds up with inanimate objects like tapping a glass or running your finger up to the strings of the piano, banging on the piano or whatever it was. We did and we ended up with about twelve pieces of music. That was about a year’s worth of work putting those twelve pieces together and we’re starting to get some attention from it.

That’s the thing. Are you a guitarist-drummer or keyboard-plucker?

Guitar. A little bit but not a lot.

I tried. I went to music school so I’m an overeducated rock drummer but I got little fat fingers. I’d pluck things out. When I was writing songs, I had a publishing deal for a little bit, I would come with a title, a storyline or a hook. When you get in the room and with Nashvillians, you’ve got three people in the room. One guy’s a great singer who’s great at Pro Tools, one’s a great guitar player and you got the drummer who comes with the big picture. We make great producers because we see the big picture.

By the end of a couple of hours, we have a piece of music and when I tell the kids, I was like, “You can have this great skillset but then it becomes a bunch of 1 and 0 in a hard drive so you have to have the relationship with either the publishers, the managers or the music supervisors. You’ve got to get that music heard which is a relationship again.”

The way Los Angeles looks to me is different from the way I looked at Los Angeles when I first began commuting out there. When it was still a big rhythm section town and there was still a lot of session work to do out there. There still is but film and television primarily are the bread and butter but then there’s also the project studio that everybody has to have out there. There are tons of remote work and that was what we built our studio to provide. It was remote work for our clients but for Windy and myself. The fire took our home, the studio and everything to our names away. Our journey as a newly married couple was to come back out of these ashes, put all of this back together and resume a career prior to COVID. It’s been unbelievable, Rich. It’s been a crazy journey.

Between the fires a couple of years ago in Los Angeles and the COVID, you were talking about seasons of life and finding destiny. It’s thick skin. You have thick skin and you can persevere because you’ve done it time and time again in the music business. I don’t even know if you wanted to talk about that.

I don’t mind talking about it at all. It was one of those incredible days. I was in Memphis recording. I was doing a session and I got a call from Windy early in the afternoon or late morning and she said, “There are fires going on out here. They’re saying it’s not going to impact us but I’m getting scared. I’m keeping a close eye out and listening to what everybody is saying. I’ll keep you posted.” I’m going, “Please do,” and that was about all I gave any thought to. I wasn’t terribly worried about it.

She called back in the middle of the afternoon and she said, “Now the fires in Box Canyon,” which is a bit East of Woodland Hills. I’m thinking, “That’s not good. That’s starting to get closer. I don’t like that. Keep me posted.” She’s like, “I’ll keep you posted.” Long story short, later that night, the evacuation was suggested. Prior to the mandatory evacuation, she started noticing that there were people that were loading their horses in their horse trailers to get their animals out of there. She said, “That’s it. We’re out of here.” She said, “What do you have to have? In case a fire does come, what do you want me to grab of yours?” I said, “Grab this guitar, that guitar and that snare drum. Don’t worry about cases. Don’t worry about any of that thing. Grab that stuff. Throw it in my car. My car’s the biggest of the two. Put everything in my car and you guys, get out of there.”

I’m sorry. I don’t know what the California law is as far as earthquakes and fires. They’re common. Can you insure against those things? Even still, you’re losing precious things.

If you’re at a level of success, you have nothing to prove. Share on X

We have fire insurance. We had our homeowners’ policy. Almost everyone will tell you what an insurance company will sell you is underinsured because they don’t want you to think that you can’t afford their product. The best way to write it is to underwrite you. While they’re underwriting you, they’re underwriting you if that makes any sense. We were underinsured. Had the fire been natural like a lightning strike or something like that, I don’t know what would have happened to us. That would have put us in a tough spot. We couldn’t have afforded to rebuild.

Because the utility company is guilty of causing it, we were in a lawsuit that will compensate for what our losses were but that’s a lawsuit that is still not yet settled. We’re moving forward completing this home but we don’t have enough money to finish it. We’re going to have to borrow money to finish the house. The process of building the house and studio back has been unbelievably expensive because of all the new codes, the seismic codes. Everything associated with building the house back is so much more expensive. Our building budget doubled from the time we started construction.

It’s such a magical place that I’ve always been attracted to. It’s one of these energy points in the world and it’s the most desirable atmosphere as far as the blue sky, sunny and 70. You don’t even need a weather person. It’s like, “What a strange job.” It’s going to be sunny and 70. The Santa Ana winds are fierce. Every year is a windy season.

When those start to blow, that’s PTSD for us. Particularly, it’s hard on her. She’s frightened of it. My farm here in Tennessee was hit by a tornado in 2008. I’ve been through a natural disaster before. I’ve got a little bit of conditioning from that and went through the PTSD fear thing associated with that but nothing could have prepared me for how horrible a fire is. There’s nothing like it.

I’m sorry.

I appreciate that. The good news is we’re coming out of it. It has tested our marriage, our professions and whatever our spiritual strength is derived from. It’s been a real challenge about what it takes to live. It’s like, “How bad do you want this, whatever this is?” For us, this is we want our home back. This is we want our ability to do our work again in our studio. We want that back. The things we lost that can’t be replaced are gone. Our heirlooms and family things, there’s nothing we can do about that. That has taught me the greatest lesson of all, which is there’s no problem with traveling light. I don’t need 30 drum sets. Let me have 2 or 3. Whatever it is I need to do my job is all I need. That teaches you. I’ve learned a lot about patience. Getting building permits in LA county will test a man and a woman. That’s tough as it gets.

It’s like getting that beer or liquor license for a restauranteur, it’s difficult.

We made it through that. We’re 70% of the way on the construction. We are seeing the light at the end of the tunnel, which is the blessing in it all. When it’s over, we’re going to have a safe home to live in and I’m grateful for that. I’m grateful for whatever the future brings us. We keep surviving somehow.

We not only survive but we thrive with our given circumstances, the gratitude and humility combined with a work ethic. It’s like, “I’m going to meet a drummer probably today and tomorrow that are better than me but I’m going to show up first and I’m going to be the last one to leave. I’m going to be super happy to be there. I’m going to keep showing up.”

That’s 90% of it. The ability to play, you got to have that. The greater challenge and the greater importance falls on the way that we interact with the folks we’re doing these records with and doing tours with. It is a family.

I can’t wait to see my guys. We canceled our Live Nation show. I jumped on a plane out to Los Angeles and I went from seeing my girlfriend in a bicoastal relationship twice a month to seeing each other 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for 365 days and we grew as a couple.

It was a lot about, “Is she the one? The answer is yeah.”

It’s been taxing on a lot of relationships whether they’re new or established.

It’s difficult.

You like diecast hoops. That’s not this show but I will tell everyone you sent me the link. Rolling Stone has been doing this amazing thing where they do a spotlight called Unknown Legends. Andy Greene did a great piece on you. It’s like a career retrospective. Nice interview and there’s tons of video footage of you with mostly long hair. There’s one little period where you had a little short haircut with Frampton.

I had that a little bit with Knopfler around the same time. I don’t know why I did that. I felt like I needed to cut all my hair off and see what that looked like for a minute. Here’s what I do want to talk about. This is slightly new for me anyway. I have been employed by Craviotto Drums to run their A&R department.

That’s fantastic. You’re consulting.

I’m a drum guy now on the other side of the glass. I’m stoked about that. I’m excited about their drumline called the Diamond Series. It’s a plied shell. It’s Sam Bacco’s baby. Sam is running Craviotto Drums now. He’s the only guy that I’m aware of in the United States that would be qualified to do that. He’s doing such a great job. The entire operation is here in Nashville now.

Lessons From A Lifer: We not only survive, but we thrive with our given circumstances.

You were friends with Johnny.

Johnny came to Neil Young’s ranch in ’88 and I was working on a Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young album. He showed up in his pickup truck with the first four drums that he ever made called Solid. I don’t know if you ever played any of those.

Greg Morrow always tells me about Solid snares.

I got to see the first four that he made. Johnny and I were friends from then on. We always remain friends. I left Drum Workshop to play for Johnny. That was a heartbreaking breakup but it was the right thing for me to do creatively at the time. It’s probably not the best business decision I ever made but it was absolutely the best creative one I made. I’ve always had this love brotherhood thing with Johnny. As wacky a guy as he was, he was a consummate drum maker. I’ve always been in love with those drums. I’m happily back with those guys and playing the drum set again.

You left Pearl now.

The reason I went back is that they offered me a position that I couldn’t say no to. I’ve never had a problem with Craviotto Drums at all. I had a problem with the fact that Johnny died. I don’t know how to go along with that. That signaled some change for me and I didn’t do anything straight away. I tried to do a thing with Pearl, which was great. They’ve got some lovely new gear out there. It’s terrific. I was proud to do some promoting for them but then this offer came. The first person I called was the head of A&R, John, over at Pearl. I said, “John, this is what’s going on.” He was sweet. He said, “You can’t not do that. You got to go.” I said, “I got to go.”

Are you going to start targeting players in Nashville to make sure that you stock the pond across the metal guys?

Yeah. I’m in the process of the early stages of all of that. It can’t just be about Nashville guys. That wouldn’t be right. The jazz guys love Johnny’s stuff but then there’s also a bunch of cats out there that aren’t necessarily jazz guys that love Johnny’s stuff. The problem with Johnny’s stuff, if there is one, is that the custom kits are expensive. That cuts a wide swath of guys that are not going to go there. They’re not going to spend that money to do it.

I remember being out there with Chris McHugh on the Keith Urban tour. We were opening up and he’s like, “Come sit up here and play these drums. Those are $12,000.” I’m like, “Holy cow.”

They’re expensive. That’s not practical for most professional drummers. It’s not in the cards. What they’ve done wisely is Sam conceptualized this new plied shell that is fantastic. That’s going to make it a lot easier for the young cats to jump in, at least get in the water, start somewhere and then they can build out from that.

As long as I’ve been doing this, I feel excited about the idea that I can go travel around the country and go look for some young guys that are bringing it. I want a home that spiritually lines up with what the Craviotto Drums company is all about and what it aspires to be from here forward. The fact that it’s Nashville-based now makes me proud of Nashville and Craviotto. It’s a cool thing.

You have all the knowledge and experience to pull from. I feel like the best A&R guys are the ones that are real musicians that have a playing history and can understand the psychology of what a touring drummer is going to need. A lot of high-end gourmet drums, sometimes the problem is, “If I’m in Peoria or Fargo, can I get this piece of hardware that I need tomorrow?” The answer is many times no. That’s sometimes the only challenge but it sounds like you’re going to crush it.

We’re steaming toward having solutions for covering things like that. Are we ever going to have the degree of backline coverage that Pearl would have? No. I don’t even know how many backline kits in the world are sitting there waiting for a Pearl artist or our drum workshop for that matter. These guys are the big fish in the pond and so be it. That’s beautiful. In all of the primary markets and secondary markets, we’re going to cover that. We’re going to get to that place.

What a lot of folks don’t know is that these big companies have to provide the sound checks,the SIRs and all these backline companies with these drums because the artists are going to come in and are going to request these drums. They’re going to do this grassroots marketing on The Tonight Shows, Today shows and the Good Morning Americas. That’s expensive for a company to provide drums to all those different vendors.

Craviotto, for a long time, couldn’t do that. They couldn’t produce that much product to even cover the backline needs. Now there’s a plan in place to be able to do that. Not only that but to be able to put amazing drum sets in there that anybody would be thrilled to get behind and play.

I’d love to hear it. It sounds like you’re in a great spot in the sense that once you get through this, you have a beautiful new home waiting on you. You’re living in two cities. You got this cool brand new job and you’re composing now. This is a little thing that’s going to bring you into your next twenty years. I feel like you’re in a great spot and a great season in your life.

I’m in a good place. Once the COVID cloud lifts and we can all get back on the tour bus and get back at it, I’m excited about getting to do that again. I’m excited about all the opportunities that are ahead. All kinds of stuff are brewing. Ironically, it’s happening at this stage of my life. I would have thought by now that as long as I’ve been doing it, the sun might be setting a bit and that is not the case. The sun’s only going to set if I decide it’s time for the sun to set but that’s not where I’m at.

You’re not the retiring type.

Being nice to people goes very far. Share on X

They’ll find me. I don’t know where they’ll find me.

I’ll die with the sticks in my hand, for sure.

I don’t want to stop this. This is my hobby. It’s not just a gig.

It’s a calling for you. You have that it-factor. The fact that you’re self-taught, that’s proof that playing along with records is amazing training. That’s probably how you started and it got that R&B, soul, rock and roll groove into your DNA.

The first time I worked with Joe, an influential record for me was a record called Barnstorm, which was a pet band of Joe. Joe Vitale, Kenny Passarelli and Joe made this amazing record. I sat with my record player right to my left and these crappy old headphones. I must have played along to that record ten million times. I would have never dreamed that I would end up playing for Joe. A little further down the line, circling back to Joe Bob, I would have never dreamed I’d be in a band with him. I’ve told Joe Bob that a million times like, “You drumming on this record was a big deal to me.” We talk about it occasionally. Whatever your training is, if it’s self-taught, you’re going to gravitate to what you’re moved by. That’s what you’re going to play. It could have as easily been a Miles Davis record.

Kind of Blue is everybody’s first jazz record.

I didn’t know which way that was going to go. It presented itself.

Kenny’s got a book. Liberty’s got a book. Joe Bob’s got a book. Is there a book in you?

Eventually. I’m hearing that question more and more. God knows I’ve got a few stories. Maybe I’ll sit down with somebody and do that sometime. My kids would enjoy that.

Forget about karma. It’s all timing. The world will tell you when it’s time to do it. I don’t think you should write a memoir before 60. I feel like at 60, you have a perspective. It seems like a magic number.

My arc has crossed the 60 line.

I don’t know what you were doing at that age but there’s a slight panic like, “I’ve achieved a lot of my childhood dreams. My parents are happy. I got a roof over my head. How long am I going to be here? Twenty years? Thirty years? What’s the plan? Am I going to be okay?” There’s a little bit of anxiety, fear and panic about getting the black balloons at the party.

I’m thinking about what you said. At 50, I would have started a long run of work that began when I left Knopfler and then subsequently started with Neil again. It was around that time. That began about a four and a half year run with Neil, 2 world tours, 2 or 3 records. It’s like a blur. I was doing the same thing because I was on a hiatus from touring. I was feeling that thing like, “I’m through touring. I’m not sure I’m going to do this anymore.” I felt that in my bones. A few years of that and I suddenly realized, “I’m not done with touring. I miss it.” It’s got to be both. I can’t do one without the other.

I wore a Stax Records shirt for you.

That’s a good T-shirt right there. That’s how I learned. The founder of Stax and his partner taught me how to do sessions.

That was a great early education to get. We all learn in our own ways. I learned on bandstands but I also learned academically. When you’re in college, you got a ten-page chart and you got to figure out how you’re going to play spang-spang-a-lang at warp speed, hit all the figures, play the dynamics and then turn the page. Now I’m going back and I’m playing along with these records like Stax and Motown. I’m rediscovering these things, the Saturday Night Fish Fry guy. He was an early rock and roller guy. We’re losing many like Little Richard and Fats. The piece of history is disappearing.

I got to do a session with Little Richard many years ago. It’s a cute little story. I was blown away that I was in the studio with him. He came to the session but he didn’t want to play. He was reluctant to do that. He stayed in the control room and we’re out on the floor. He wanted another keyboard player there to cover his bit. Reese Wynans was there. We’re working on this track up and Little Richard keeps getting on the talkback. He keeps telling Reese, “Maybe try this.” This went on for a little while. Finally, Reese might have been the first person to say this. He goes, “Why don’t you come out here and play me what you’re hearing?”

He wanted to sing but he didn’t want to play.

He wanted to just be there and then he would do his singing and stuff after the fact. Reese cleverly got him to come out to the piano. When Little Richard got to the piano, now Little Richard is playing the piano. I got it in my head. I was like, “I’ve got to see if he’ll sign my snare drum.” I went to his handler guy and I said, “Is there any possibility that Little Richard would autograph my snare drum?” He said, “He didn’t do stuff like that.” I said, “I’m sorry. I’m a huge fan and it would mean the world if he was willing to do that.” He goes, “Let’s wait until we get the song. If everything’s cool, I’ll mention it to him but I can’t guarantee it.” I thought, “He’s not going to sign this thing.”

Lessons From A Lifer: You have to have the ability to play the drums, but the greater challenge and the greater importance falls on how we interact with the folks we’re doing these records with.

We finished and we got the track. Everything’s good. Everybody’s happy. The guy comes up to me and he goes, “I want to let you know that Richard’s going to sign this but he needs to speak with you personally before he signs this drum.” I went, “Okay.” The session is over with and I go and sit down with him. He looks me dead in the eye and he goes, “Before I sign your drum, there are things that I’d like to share with you.” I went, “Okay.” He gave me his personal testimonial as a Christian that was important to him to share with me purely like a preacher. He wanted to talk to me about God. He finished his thing and then he handed me this little tiny Bible. He put that in my hand and he goes, “Now I’ll sign your snare drum.”

He wants to touch a certain number of people every day spiritually.

He was all about that.

He’s up there entertaining the angels.

He’s talking about eighth notes.

He’s probably telling them all about what a-wop-bop-a-loo-bop means. That Saturday Night Fish Fry was Louis Jordan. This was great to spend time with you. I know drummers, we close joints down. It was nice to spend this time with you. After being in the industry for many years, I never got to talk to you for this length of time so I appreciate it.

It’s a pleasure and I appreciate you thinking of me. Let’s not let this go by too much longer before we do it again.

Let’s do it. I’m pulling for you and with the house. Maybe we’ll have an ice-cold Martini in Calabasas.

Let me tell you right where that’s going to be. There’s a restaurant on PCH and Trancas called Kristy’s. It’s the best Martini in Los Angeles.

This is going on the top of my to-do list. As soon as I get my second vaccine and the world starts coming to life, we will do it.

Count on that.

Thank you for your time.

You’re welcome, Rich. Be safe. Be well.

To all the readers out there, I got an email address for you, [email protected]. As always, be sure to subscribe, share, rate and review. It helps people find the show. I appreciate it. Thanks. Keep coming back for the good stuff. We’ll see you next time. Thanks, Chad.

You’re welcome, Rich. See you soon.

Important Links:

- JimMcCarthyVoiceovers.com

- Chad Cromwell

- Drum Paradise

- Windy Wagner

- Joe Walsh

- Eddie Izzard

- Joe Vitale

- Peter Gabriel

- Ruben Blades

- Amotz Plessner

- Unknown Legends

- Piece – Drummer Chad Cromwell on His Years With Neil Young, Mark Knopfler and Joe Walsh by Andy Greene

- Craviotto Drums

- Diamond Series

- Pearl

- Kristy’s

- [email protected]

About Chad Cromwell

Chad Cromwell was born in Paducah, Kentucky, on June 14th, 1957. When he was three years old his family moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he grew up. He started playing drums at the age of eight, wearing headphones as he played along to records in an upstairs room of his parents’ home. By the age of twelve he was playing in garage bands in the local neighborhood.

Chad Cromwell was born in Paducah, Kentucky, on June 14th, 1957. When he was three years old his family moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he grew up. He started playing drums at the age of eight, wearing headphones as he played along to records in an upstairs room of his parents’ home. By the age of twelve he was playing in garage bands in the local neighborhood.

Among Chad’s early influences were drummer Al Jackson and the artists of Stax Records, and artists such as Al Green on Willie Mitchell’s Memphis based label, Hi Records. Jim Stewart, founder of Stax Records, along with Bobby Manuel, started a production company called The Daily Planet after the sale of Stax. Chad “hung out” and subsequently worked for The Daily Planet and learned more about rhythm and recording than anywhere else thus far. In fact, Jim and Bobby were key influences on Chad’s style of drumming.

In 1975, upon graduating high school, Chad flew to London to join two Memphians who already had gigs. Dave Cochran was playing bass for Chris Spedding, and Robert Johnson (not the legendary) was playing with Jon Entwhistle in Ox. Robert had been offered a record deal with Elton John’s label, Rocket Records, and called fellow Memphian, Chad, along with David Cochran to record as Lash LaRue.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the RICH REDMOND SHOW Community today: